Alice Munro’s story shows it’s time for a child protection revolution

Many lives were upended last year when Andrea, a woman in her late fifties publicly shared a long-suppressed testimony of a taboo violation. Aged 9 she traversed the logistics of parental separation by travelling across Canada to spend the summer with her mother. When summer was over, Andrea returned home to her dad and shared a secret with a sibling. Her mom’s new partner had molested her. Soon the whole household knew. Andrea’s dad forbade anyone confronting her mom or initiating action against the abuser, though he took measures to ensure it never happened again.

Sixteen years later, aged 25 Andrea finally told her mom. As feared, rather than showing empathy her mom primarily felt aggrieved by the partner’s betrayal. She left him momentarily but soon returned.

Older abuse survivors would recognize this sequence of events as just the way things were done in the 1970s. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s the anglosphere found a vocabulary to discuss child sex abuse, despite it affecting one in five girls and eight percent of boys.

In 1984, sixty million Americans watched Ted Danson play an abusive father in Something About Amelia, the first major television drama about child sex abuse. Helplines for child victims were swamped and soon publications like Newsweek ran their first ever cover stories on the theme.

Prime-time BBC in the UK broadcast a special called Childwatch in 1986. Britain’s most popular broadcaster, Dame Esther Rantzen, opened with a bombshell.

“Childwatch has undertaken one of the biggest national surveys into cruelty to children. Tragically, well over one million children in this country are suffering now because of cruelty . . . victims like Catherine who want today’s children to get the help and support she never had.”

Aghast viewers, who never heard anything like this before, saw the camera cut to a silhouetted woman describing childhood abuse she had never told anyone about. Rantzen spoke directly to children watching at home and told them if they were being abused, they weren’t alone, and it wasn’t their fault. Childwatch launched a helpline and just as with Something About Amelia in the US, the lines jammed after the broadcast.

This cultural shift turbo-charged policy. Child protection investments increased and barriers to reporting abuse were removed. Annual US reporting of child abuse and neglect increased from 60,000 in the mid-seventies to two million by 1990. Population surveys showed increased reporting accompanied decreased abuse in the US and Canada. This taboo-busting revolution measurably improved millions of children’s lives, but the revolution is unfinished.

Andrea told her story soon after her mother had died at the age of 92 last summer. Her mother was author and Nobel Laureate Alice Munro and the lives upended were readers who made sense of their own lives growing up through Munro’s empathetic, relatable writing. It was a shock to the system. As the US author Rebecca Makkai said of Munro’s indifference to her own daughter’s abuse“the revelations don’t just defile the artist, but the art itself”.

A Canadian colleague who has campaigned against child abuse globally asked ‘do you think it’s still okay to read her writing?’ The public discourse was shaped by headlines like ‘global literary community is reeling from Munro’s failure to protect her daughter’. Readers couldn’t process a conflict between the empathy in Munro’s writing and the brutal dissociation and neglect that so harmed her daughter.

The revelation didn’t ignite public curiosity about the prevalence, impact and aggregated public costs of this type of trauma. Not just the sexual abuse itself, but how the absence of an attuned parent leaves a child vulnerable to harm.

The Buffer

The primary protection for a child from harm or exploitation is an attuned parent. Nine out of ten of the early UK Childline callers, whose stories of sexual abuse are recounted in Dame Esther Rantzen’s 2011 book Running Out of Tears, also suffered what we would describe today as emotional neglect from the non-abusing parent. They lacked a protective buffer. In the tenth case, the parent intervened immediately, confronted the abuser and soothed the child.

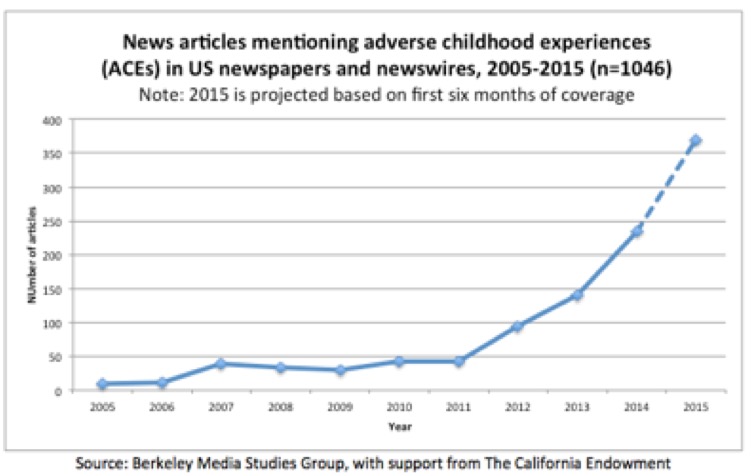

The taboo that was broken in the mid-80s was on child sexual abuse, an unambiguous criminal act with intent to harm the child. In 2025 we also know the damage done by other adverse childhood experiences too, including physical violence, emotional neglect, living with addicted parents or witnessing domestic violence. But we know the causes and solutions too and are the first generation in history to know how to prevent child maltreatment at scale.

.Child maltreatment doesn’t only happen in chaos and rage-filled homes or where poverty is present. More than half of adults experienced a potentially traumatic incident at home in childhood. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) studies from 37 diverse countries show 57% of us endured one of 10 listed categories of household violence, neglect or dysfunctional parenting. Around 15 per cent have an ‘ACE score’ of four or more. The prevalence is similar across countries, continents and even generations with similar ACE scores from those who grew up in the 1940s or 1990s. This entrenched endemic of child maltreatment is more prevalent than Covid at its height.

Yet it is hidden in plain sight, and for understandable reasons. Those affected live with internal shame, fear of external stigma and conflicting feelings of loving our parents and hating the pain they cause us. This scaffolding of silence is underpinned by myth: children should be seen and not heard (a license for neglect) and spare the rod spoil the child (a license for abuse)

It’s a costly problem to hide. The US Centre For Disease Control (CDC) measures the 40 most important health and wellbeing outcomes across every US state. The higher the ACE score, the worse the outcome on every measure.

Data from Wales shows adults with high ACEs are four times likelier to be alcoholic or develop diabetes, 14 and 15 times more likely to be a victim or perpetrator of violence respectively and 20 times more likely to end up in prison. High-ACE teens are the type groomers, gangs, radicalizers, and drug pushers seek to recruit.

At a very conservative estimate, adult outcomes of adverse childhood experiences cost around 8% of GDP, trillions of dollars.

Most can rationalize a correlation between a Dickensian childhood and a life of addiction or crime, but how do we explain worse health and wellbeing outcomes?

When children experience anguish and fear, unbuffered by parents or teachers, they endure what Harvard scientists call toxic stress-the chronic elevation of the stress response system. This wreaks havoc on the fragile and evolving neurobiology of the child, leaving an imprint of trauma, low self-esteem and hyper-alertness to threat. Toxic stress in childhood derails normal human development and is especially dangerous if not addressed before adolescent brain development kicks off the riskiest phase in the human life cycle.

Emotional neglect is as harmful as physical abuse. Children have a biological need for a deep bond with a primary caregiver, its absence is terrifying. For children danger is not just the presence of violence, it is the absence of love. Often it happens because the parent is unwittingly just replicating what they experienced as children themselves This is intergenerational trauma. But it is beatable.

If I saw the BBC Childwatch broadcast, it would have been through a shop window. I was 15 and living on the streets, having fled a violent UK inner city children’s home. Decades later and after some therapy and healing, I held our newborn son in a New York maternity ward. As I held him on my chest, his tiny head against my beating heart I knew what happened to me as a child was now unimaginable to myself. I would walk to the end of the earth for him to feel safe and loved. The inter-generational cycle ends with me. The more I held him, read, and sang with him, the further away that desolate children’s home and the torturous remnants of its memory felt. This is because love heals.

But it begged a question: if I can end the cycle can everyone end it? Could we prevent it at scale? Many child development and public health thought leaders think we can.

Child Development Revolution

The former British Conservative party grandee and A-list podcaster Rory Stewart recently lamented that 21st century technology fails to drive positive human outcomes the way 20th century advances like piped water or vaccines had.

The best example of a 20th century breakthrough is the Child Survival Revolution. In 1980 American epidemiologist Dr John Rohde wrote a paper arguing 14 million children die annually due to three problems already solved in the industrialised world. 1) Children were not vaccinated against major diseases 2) Families couldn’t access oral rehydration solution for acute childhood diarrhoea and 3) Early nutrition wasn’t protected by breastfeeding promotion or routine growth monitoring.

If governments sharply focussed on universalizing these three interventions, child deaths would plummet.

Despite acute cold-war polarisation, disparate governments coalesced on saving children’s lives. Prime ministers and royals, health systems and village doctors joined the world’s biggest ever public health campaign. Vaccine coverage of under-fives leapt from 15% to 80% in a decade and soon child mortality was halved. Today millions of children live each year because of the Child Survival Revolution, perhaps modern humanity’s greatest accomplishment.

But it almost didn’t happen. Opposition and scepticism were prolific. All the 20th century advances Stweart celebrated were once harebrained, unimaginable dreams. In a Growth A History and a Reckoning, Daniel Susskind reminds us even the concept of measurable economic growth driving our modern political economy and culture, was unimaginable for 99% of human history. Tap water, antibiotics and road safety were all nuts’ ideas once.

Ending child maltreatment is not just a challenge for the global south, it’s universal and may seem insurmountable at a moment when we are more polarised than ever and our ability to focus is battered in an attention economy. Bur the world needs a new idea to build shared purpose. Reformed polarizer and pollster Frank Luntz argues the only cause with potential to de-polarize politics is children. Bipartisan interest from JD Vance to Gavin Newsom in the costs and prevalence of ACEs suggest we are ready for a new child revolution. Like many public health campaign, it needs three components: Prevent transmission, treat those affected and ensure everyone is aware of the risk

Primary Prevention

Scientists at Oxford and World Health Organisation recently completed a study potentially as impactful for child development, as John Rohde’s paper for survival. They rigorously reviewed evidence-based parenting programs delivered through home visits or group sessions to build parenting skills and knowledge. The home visitor doesn’t impose or judge the parent. If the parent has strong attachment and development skills already, the home visitor builds off these strengths.They assessed 435 trials from 65 countries and found improved outcomes in responsive caregiving, maltreatment reduction, learning and behaviour.

The review also found a telling, unintended benefit of the programmes. An improvement in parental mental health. One of the explanations is when parents can bond with their child, as I did with my son, the emerging relationship is reciprocal and healing. Anyone returning home from a stressful day with a horrible boss or client and soothed holding their child know this. Again, love heals.

When we had our son, there was no parenting program offered. In any given year there are over 600,000 babies born in the state of New York. According to the National Home Visiting Service, only 14,000 receive home visits yet 63% of children in the State have at least one ACE. Home visits need to be universally available and supported by decent parental-leave and perinatal health care as pre-requisites for primary prevention.

The Antidote

When children feel unsafe or unloved at home, the next best hope is an attuned teacher. We now know that healthy relationships are the antidote to toxic stress. They literally de-activate the stress response system. Extensive research shows healthy relationships with teachers are the leading driver of good learning outcomes for all children. For vulnerable children they provide a layer of protection as a foundation for healing and learning. I would not be here today writing this if it wasn’t for a teacher Jan Rapport, who eventually helped me see a pathway to a better future.

One of the world’s leading authorities on child development, Professor Peter Fonagy describes this as epistemic trust. As a lone refugee child from Hungary in 1960s London, Professor Fonagy recalls how the simple act of his teacher gifting a book to each child in the class was transformative in helping him cope with the trauma and focus on his studies:

“She gave them out randomly. But, at the same time, we all felt recognized by her. We all felt that she treated us as individuals, and we all had our minds wide open to her.”

Can we systemise healthy relationships in school without overburdening already stressed teachers? Educationalists at Harvard developed a simple approach for school authorities called Relationship Mapping. Every teacher in a school goes through the register and puts a yellow dot next to a child they know has healthy relationships. The school then intentionally works with children who have no yellow dots at all to link them up to healthy relationships. The goal is for no child to be unseen. It’s not rocket science, but it is brain science. The absence of healthy adult relationships is the major risk factor for teens.

Ensuring every child has healthy teacher relationships should start in pre-school as the child’s brain development and sense of self and the world is growing most rapidly. If we are serious about preventing risk, it should be especially robust as children enter adolescence. For children with acute vulnerability, we need well-resourced, high quality social work and mental health support.

Awareness

The earliest research on attachment had a key finding. Parents who were able to process and understand the trauma they had experienced as children were less likely to transmit it to their own children.

I thought about at this at the third birthday party for one of our son’s pre-school classmates. As our children bounced up and down in unison to Baby Shark, a group of dads discussed modern parenting when one chuckled

“I love my parents, but no way am I giving my kids the trauma they gave me!”

It wasn’t a heavy conversation, everyone laughed and agreed. But that conversation wouldn’t have happened a generation ago. Evidence based parenting apps and books on nurturing care, child development and trauma are devoured by an educated minority. It wouldn’t take much to make that knowledge universally available, so everyone is aware of the risks of child trauma the way we are aware of Covid, HIV or smoking. Through public awareness campaigns that ensure a conversation in every communityand mainstreaming mental health and child development in schools, we can provide the vocabulary and understanding to prevent transmission of child trauma.

Making these three interventions universally available to parents, school and children everywhere would cost a fraction of the trillions we lose globally each year to the negative outcomes of child maltreatment. It is not enough to be the first generation in history to know the causes and solutions to child trauma we need to be the last to accept it as intractable or insurmountable.

Every major gain in child protection over the past decades has come after a shocking public revelation or tragedy. It would be a fitting tribute to Andrea’s courage to harness the shockwaves her testimony caused to ignite a child protection revolution that ensures every child grows up safe and loved.

Benjamin Perks book Trauma Proof: Healing, Attachment and the Science of Prevention is out in North America here and in the UK and Commonwealth here

You must be logged in to post a comment.